Errikos Frantziskakis

(1908-1958)

ΕΡΡΙΚΟΣ ΦΡΑΝΤΖΙΣΚΑΚΗΣ

(1908-1958)

ΕΡΡΙΚΟΣ ΦΡΑΝΤΖΙΣΚΑΚΗΣ

A Votary of Painting

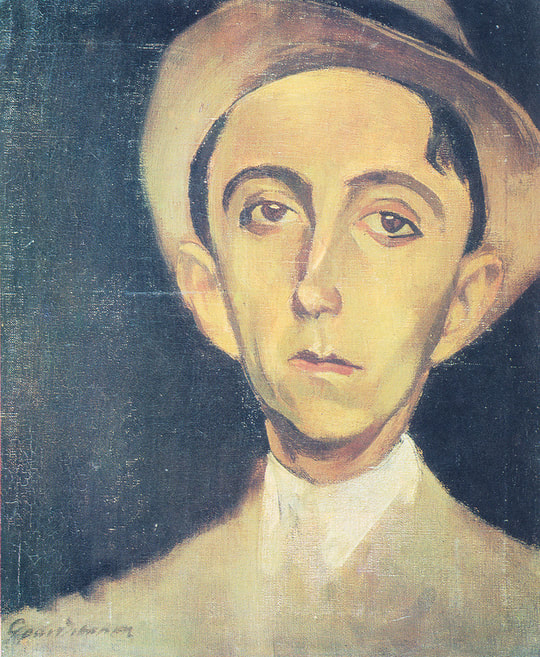

Errikos Frantzeskakis in 1947.

Errikos Frantzeskakis in 1947.

He was born in August 1908 and in August 1958 he died. The tangible evidence of his life's work is scant: thirty to thirty-five of his oil paintings scattered here and there, a few drawings and a series of glass objects made at the Bodossakis Glassworks during the period when he was design manager there. Was it, one wonders, because all his other activities did not leave him time to paint any more than that? For he did have many other consuming interests at one period or another: poetry as a young man, the study of the old masters in later years, teaching art to youngsters, to name only a few. This might seem to be the obvious answer, but it does not stand up to scrutiny, because none of his other interests could have induced him to neglect painting, not for a moment.

Neither poetry (which he abandoned early on, in response, as he always said, to his father's advice to choose one and only one aim in life - advice which he received on leaving Chania in 1927 for the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Rome, where, during the final three years of his studies, he was sponsored by Eleftherios Venizelos himself) nor his wanderings on Mount Athos nor his periods of contemplation at Osios Loukas, Daphni and old Piraeus could distract him from his painting.

(In Piraeus he collected a great deal of material about Konstantinos Volanakis, the celebrated nineteenth-century Greek painter, some of which he used in his monumental work Greek Painters of the Nineteenth Century, published by the Commercial Bank of Greece.)

Not one of his huge range of dearly loved hobbies and interests - his love of beautiful old objects, Byzantine music, the writings of the Fathers of the Church - made him neglect his paintings, which he saw as a demanding but enjoyable process that transforms spirit into matter and matter into spirit.

The fact is that Errikos Frantziskakis painted many pictures, but he tore them up, he destroyed them. What mattered far more to him than the opinion of other people were the dictates of his conscience: a conscience that was always on the alert, guiding him and protecting him from the temptation of simple solutions, which he despised and avoided at all costs. He was, however, introverted only in so far as his painting was concerned; generally speaking, he was demonstrative in the extreme and played a leading role in every form of artistic activity which fitted in with his credo.

In 1938, in collaboration with his friend and pupil Panos Spanoudis, he brought out the fortnightly magazine Techni in an attempt to put artistic issues within the Greek context - no easy matter at that time with the then prevailing political conditions in Greece.

A few years later, under the Nazi occupation, he wrote and published a small book, On Painting, which was illustrated with engraved vignettes by Yannis Moralis. It is a simple and lucid little handbook which, as he says, is directed primarily at painters but can be read by anyone, even non-specialists, as long as they have outstripped the "-ism" stage, for which he, a puritanical painter and devotee of the metier, felt the profoundest contempt.

He could talk for hours, endlessly analysing the religious paintings of Panselinos, the human figures of Giorgione and Tintoretto, the artistic merits of Corot or the Fayum portraits. However, he never tried to fit any of these things into a preordained pattern of human intellectual development nor to interpret them historically, encasing them in cold theoretical formulas. And in this respect he practised what he preached, because his paintings, which could be described as timeless, still cannot be pigeonholed on the basis of current aesthetic standards.

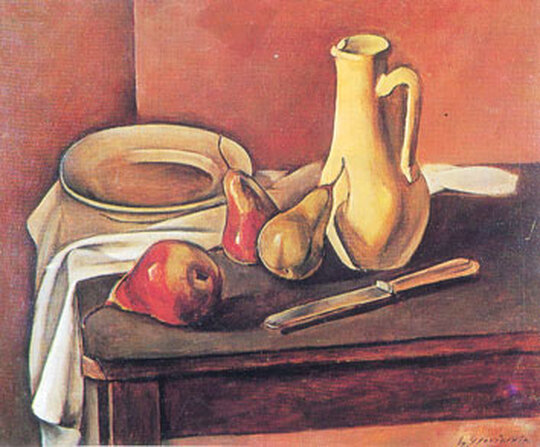

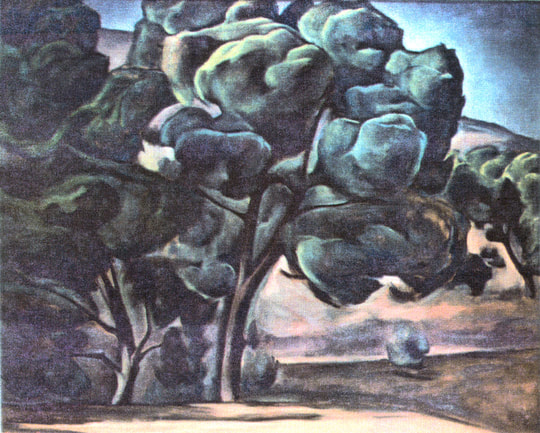

The end of the occupation marked the beginning of a new phase in his painting. He stopped doing still-lives, crowded compositions and portraits (of which, as it happens, only a few have survived, including an unfinished one of his mother) and went back again to the open country, which he had missed so much. There he was able to put into practice everything he had learnt and stored away in his mind while studying the problems of light within the four walls of his studio or under the blazing sun of Attica. He travelled now to Skopelos and Mytilini, to Pilion and Evvia, to places where the olive-tree grew - that heavenly tree that he loved above all. He would spend entire summers in one place, sitting always in the same olive grove under the trees, quietly trying to catch those rare moments, bathed in supernatural light, which shimmer in his landscapes. Rarely, however, was he satisfied with himself and so he continued to tear up his paintings.

During this period, although consumed by another passion, that of teaching art to youngsters (at D. Eleftheriadis - I.M. Panayotopoulos School) - a passion which, as was later proved, was neither short-lived nor any less intense than the others and which absorbed him from 1948 until his death - he also formed the Stathmi Group in company with ten other artist friends, and with them he showed his work in Athens and abroad - in Stockholm, Cairo, Rome and elsewhere. These exhibitions and his participation in a few Panhellenic Exhibitions were the only contacts he had with the public after the war (before the war he had also exhibited with the Techni Group). However, his work now made less impact, as by this time the atmosphere was already charged with the negative current that has led to modern trends and new lines of experimentation.

A few years later, when he fell ill and died, he was mourned by a large circle of friends and acquaintances who had all been inspired by him. They remembered a slight, wiry figure; a humorous man and a delightful conversationalist (although sometimes argumentative when called upon to defend his ideas); a craftsman who was gentle and unassuming as he worked contemplatively at his easel; a man of "the Greek East" who was and felt Greek to the depths of his soul; a lover of the Italian Renaissance with a broad-minded attitude to art; a perceptive and sensitive student of nineteenth-century Greek painting, the evening companion who was torn between the attractions of good living and asceticism; the irrepressibly enthusiastic teacher who was unrivalled in the breadth of his education and the scope of his knowledge... And his work? His work, the little work he left to us, is offered up as a prayer, a supplication to the heavens:

O Lord, Thou has searched me, and known me.

Thou knowest my down-sitting and mine up-rising,

Thou understandest my thought afar off.

FRANTZIS K. FRANTZESKAKIS

Neither poetry (which he abandoned early on, in response, as he always said, to his father's advice to choose one and only one aim in life - advice which he received on leaving Chania in 1927 for the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Rome, where, during the final three years of his studies, he was sponsored by Eleftherios Venizelos himself) nor his wanderings on Mount Athos nor his periods of contemplation at Osios Loukas, Daphni and old Piraeus could distract him from his painting.

(In Piraeus he collected a great deal of material about Konstantinos Volanakis, the celebrated nineteenth-century Greek painter, some of which he used in his monumental work Greek Painters of the Nineteenth Century, published by the Commercial Bank of Greece.)

Not one of his huge range of dearly loved hobbies and interests - his love of beautiful old objects, Byzantine music, the writings of the Fathers of the Church - made him neglect his paintings, which he saw as a demanding but enjoyable process that transforms spirit into matter and matter into spirit.

The fact is that Errikos Frantziskakis painted many pictures, but he tore them up, he destroyed them. What mattered far more to him than the opinion of other people were the dictates of his conscience: a conscience that was always on the alert, guiding him and protecting him from the temptation of simple solutions, which he despised and avoided at all costs. He was, however, introverted only in so far as his painting was concerned; generally speaking, he was demonstrative in the extreme and played a leading role in every form of artistic activity which fitted in with his credo.

In 1938, in collaboration with his friend and pupil Panos Spanoudis, he brought out the fortnightly magazine Techni in an attempt to put artistic issues within the Greek context - no easy matter at that time with the then prevailing political conditions in Greece.

A few years later, under the Nazi occupation, he wrote and published a small book, On Painting, which was illustrated with engraved vignettes by Yannis Moralis. It is a simple and lucid little handbook which, as he says, is directed primarily at painters but can be read by anyone, even non-specialists, as long as they have outstripped the "-ism" stage, for which he, a puritanical painter and devotee of the metier, felt the profoundest contempt.

He could talk for hours, endlessly analysing the religious paintings of Panselinos, the human figures of Giorgione and Tintoretto, the artistic merits of Corot or the Fayum portraits. However, he never tried to fit any of these things into a preordained pattern of human intellectual development nor to interpret them historically, encasing them in cold theoretical formulas. And in this respect he practised what he preached, because his paintings, which could be described as timeless, still cannot be pigeonholed on the basis of current aesthetic standards.

The end of the occupation marked the beginning of a new phase in his painting. He stopped doing still-lives, crowded compositions and portraits (of which, as it happens, only a few have survived, including an unfinished one of his mother) and went back again to the open country, which he had missed so much. There he was able to put into practice everything he had learnt and stored away in his mind while studying the problems of light within the four walls of his studio or under the blazing sun of Attica. He travelled now to Skopelos and Mytilini, to Pilion and Evvia, to places where the olive-tree grew - that heavenly tree that he loved above all. He would spend entire summers in one place, sitting always in the same olive grove under the trees, quietly trying to catch those rare moments, bathed in supernatural light, which shimmer in his landscapes. Rarely, however, was he satisfied with himself and so he continued to tear up his paintings.

During this period, although consumed by another passion, that of teaching art to youngsters (at D. Eleftheriadis - I.M. Panayotopoulos School) - a passion which, as was later proved, was neither short-lived nor any less intense than the others and which absorbed him from 1948 until his death - he also formed the Stathmi Group in company with ten other artist friends, and with them he showed his work in Athens and abroad - in Stockholm, Cairo, Rome and elsewhere. These exhibitions and his participation in a few Panhellenic Exhibitions were the only contacts he had with the public after the war (before the war he had also exhibited with the Techni Group). However, his work now made less impact, as by this time the atmosphere was already charged with the negative current that has led to modern trends and new lines of experimentation.

A few years later, when he fell ill and died, he was mourned by a large circle of friends and acquaintances who had all been inspired by him. They remembered a slight, wiry figure; a humorous man and a delightful conversationalist (although sometimes argumentative when called upon to defend his ideas); a craftsman who was gentle and unassuming as he worked contemplatively at his easel; a man of "the Greek East" who was and felt Greek to the depths of his soul; a lover of the Italian Renaissance with a broad-minded attitude to art; a perceptive and sensitive student of nineteenth-century Greek painting, the evening companion who was torn between the attractions of good living and asceticism; the irrepressibly enthusiastic teacher who was unrivalled in the breadth of his education and the scope of his knowledge... And his work? His work, the little work he left to us, is offered up as a prayer, a supplication to the heavens:

O Lord, Thou has searched me, and known me.

Thou knowest my down-sitting and mine up-rising,

Thou understandest my thought afar off.

FRANTZIS K. FRANTZESKAKIS

As one more indication of the inadequacies and anti-professional conducts of the Greek state in the past, the spelling of the family name of Frantzeskakis keeps changing from legal document to legal document. Thus half of the family is "Frantzeskakis" and the other half is "Frantziskakis".